Stories

Beyond the Spatial

The act of Venn diagramming using concrete walls and political boundaries, while being a strategy to win the long game, also disrupts and dictates how Palestinians live, the roads they take, and the life partners they pick. This story is one of tens of thousands which show the ongoing and systematic fragmentation of Palestinian communities in the West bank and Jerusalem. Starting a family with a person who lives within a 2-mile radius but holds an ID with a different color is not only a commitment to this person, but rather, a guarantee to live with the risk of losing everything at any moment; your legal status, access to your city, and even seeing your family. Choosing a partner with a different color ID means you are committed to sacrificing your wealth to an occupying force and your time to commute and endless bureaucratic processes. This story is not unique and definitely not an extreme one. It is an appropriate way to conclude this project specifically because it exposes the typical circumstances under which a Palestinian family is forced to establish a home in Kafr Aqab.

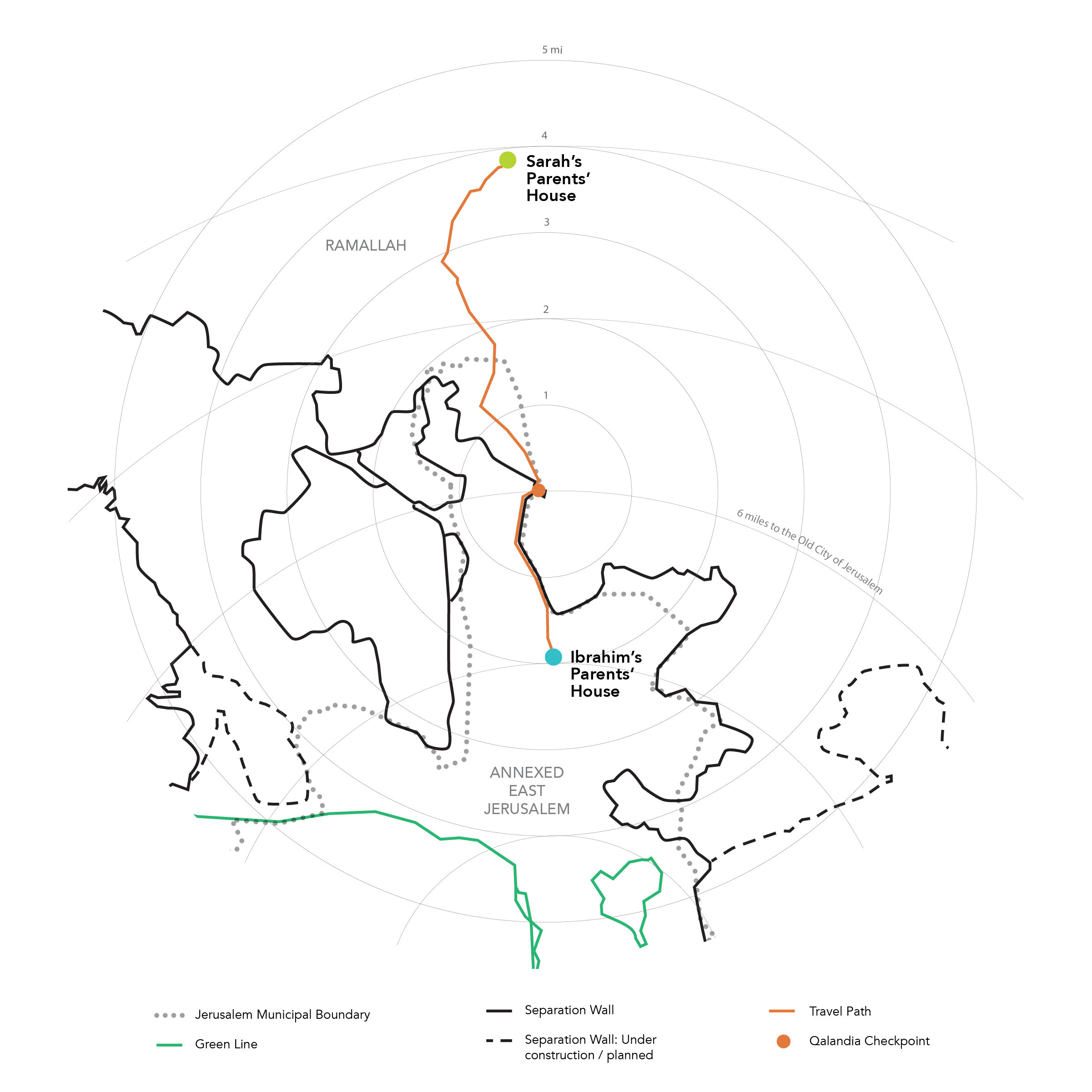

Sarah and Ibrahim (their real names are not used so as not to put them in any danger) met in college in 2010, where Sarah, with a green West Bank ID, lived in Ramallah and Ibrahim, with a blue Jerusalem ID, lived in East Jerusalem- less than 6 miles apart. Ibrahim would cross the Qalandia checkpoint daily to attend his classes and see Sarah, since her West Bank ID denies her entry to Jerusalem unless granted a special permit, which is only issued for exceptional cases.

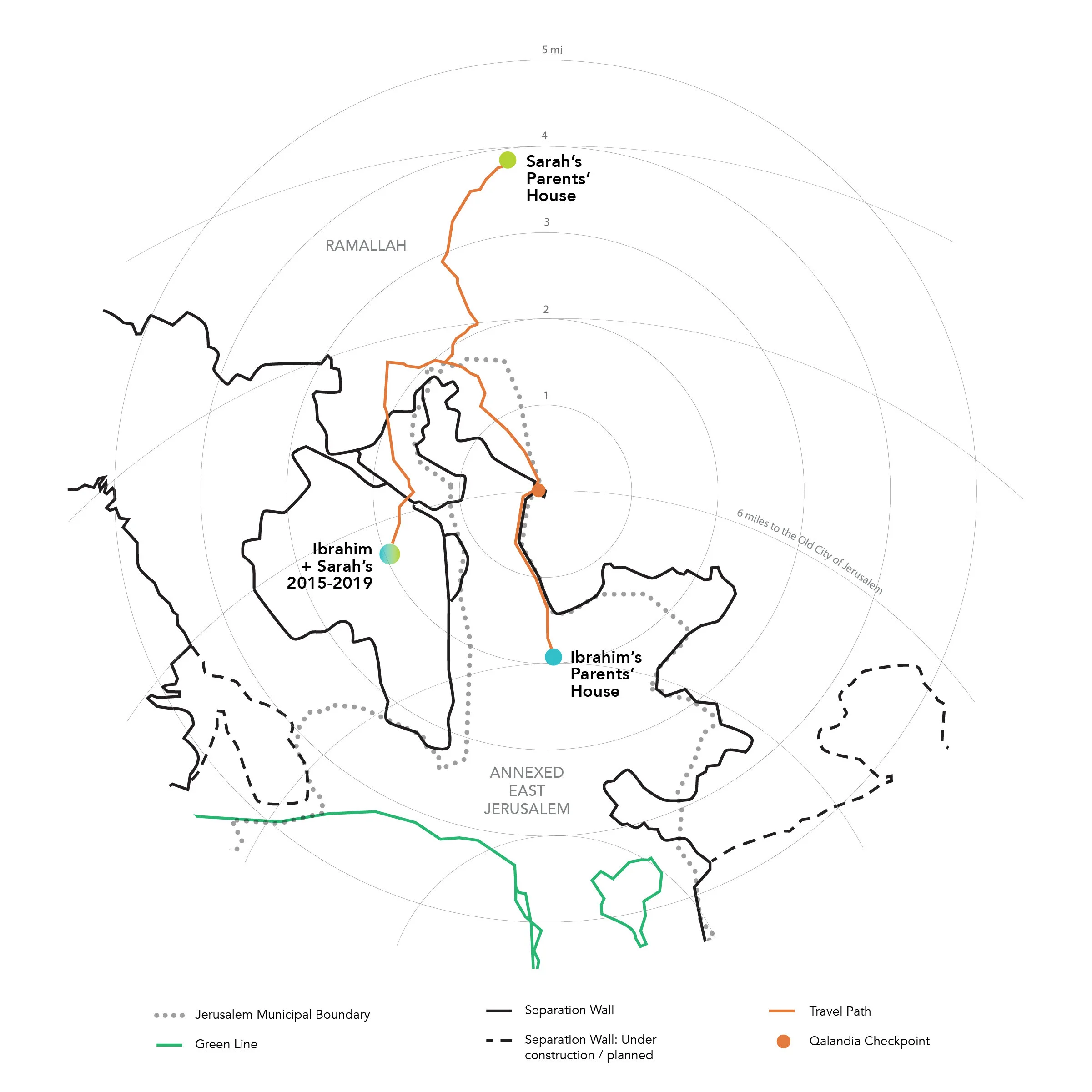

Ibrahim and Sarah got married in 2015 and moved to a three-bedroom single-family house which Ibrahim’s parents own in Bir Nabala directly outside Jerusalem. This home had been vacant since 2005, which is the year the Israeli government found out that Ibrahim’s parents -in defiance of the “Center of Life” policy- had been living outside the city boundary of Jerusalem. Ibrahim’s mother (who also holds a West Bank ID) got her temporary permit revoked and was barred from entering Jerusalem. Ten years later, the government granted her a temporary permit, which must be renewed every year, but can be revoked at any moment, and only allows her to enter Jerusalem, but not to drive or work there. To this moment and after 34 years of applying for family reunification, Ibrahim’s mother can only get to her own home with this temporary permit.

Ibrahim and Sarah lived in that house in Bir Nabala for four years after falsely registering that they live in Jerusalem with Ibrahim’s parents. Had they been discovered; different measures could have been taken ranging from denying their family reunification application to revoking Ibrahim’s ID. Ibrahim and Sarah made sure to keep some of their belongings at Ibrahim’s parents’ house in Jerusalem because the government uses extreme surveillance and actually makes rounds to ensure Palestinian Jerusalemites in fact live at the addresses they claim, not just pay their taxes and bills.

As soon as Sarah got pregnant, the risk of breaking their family evolved into the risk of having an unregistered child. They realized that staying in Bir Nabala was not an option anymore, especially that having a child or starting any kind of paperwork automatically draws attention from the government. The “ideal” solution would have been to move to East Jerusalem, but that was not an option for many reasons. First, paying rent in Jerusalem with West Bank salaries is impossible; rent only would have been 80% of their income. Second, living in Jerusalem leaves Sarah in the same position as her mother-in-law; relying on a legally fragile permit to have access to her own home while being banned from driving and working in Jerusalem. And third, both Sarah and Ibrahim would have needed to take hours out of their day to cross the checkpoint to get to their jobs, family, and friends. And so, the inevitable decision to move to Kafr Aqab was made, where rent prices are lower (although higher than Ramallah), both Ibrahim and Sarah can work and drive, and crossing the checkpoint is only needed to visit Ibrahim’s family or attend weekly client meetings for Ibrahim.

Although Sarah and Ibrahim’s income is considered within the upper-middle class range, they spend an average of 69% of their income to live in Kafr Aqab- money they were able to keep while living in Bir Nabala. For absolutely no services from the city, they pay 12% of their income as property tax. They make monthly payments of 57% of their income to pay off a loan for an apartment in an unregistered building with a price 25% higher than other apartments they found because it’s located in a “safer” area within the neighborhood.

Now, all can Sarah and Ibrahim do is wait. Wait an infinite number of years for their family reunification application to be approved. Wait to suddenly be able to afford an apartment in Jerusalem. Wait for Kafr Aqab to be excised from Jerusalem and get forced to move in with Ibrahim’s parents and share a bedroom with his brother’s family. Wait for Kafr Aqab to be excised and for Ibrahim to lose his ID, get denied access to Jerusalem and his family, or become stateless.

Final Thoughts

As architects we are trained to investigate contexts, analyze histories, understand laws and ordinances, simplify complex concepts, and anticipate human needs. Within contexts of conflict and dire injustice, leveraging those skills presents an opportunity to explore new roles of architecture, where it starts to take part in creating a narrative crucial to constructing an identity for a human cause. This identity in return, becomes the first step towards catalyzing true change.